Both large and small, the Rule’s 73 chapters contain an entire way of life.

It all began when he fled the city.

The Rule of St. Benedict, written after he fled Rome and eventually settled at Monte Cassino, consists of a Prologue and seventy-three chapters, ranging from a few lines to several pages. They provide teaching about the basic monastic virtues of humility, silence, and obedience as well as directives for daily living. The Rule prescribes times for common prayer, meditative reading, and manual work.

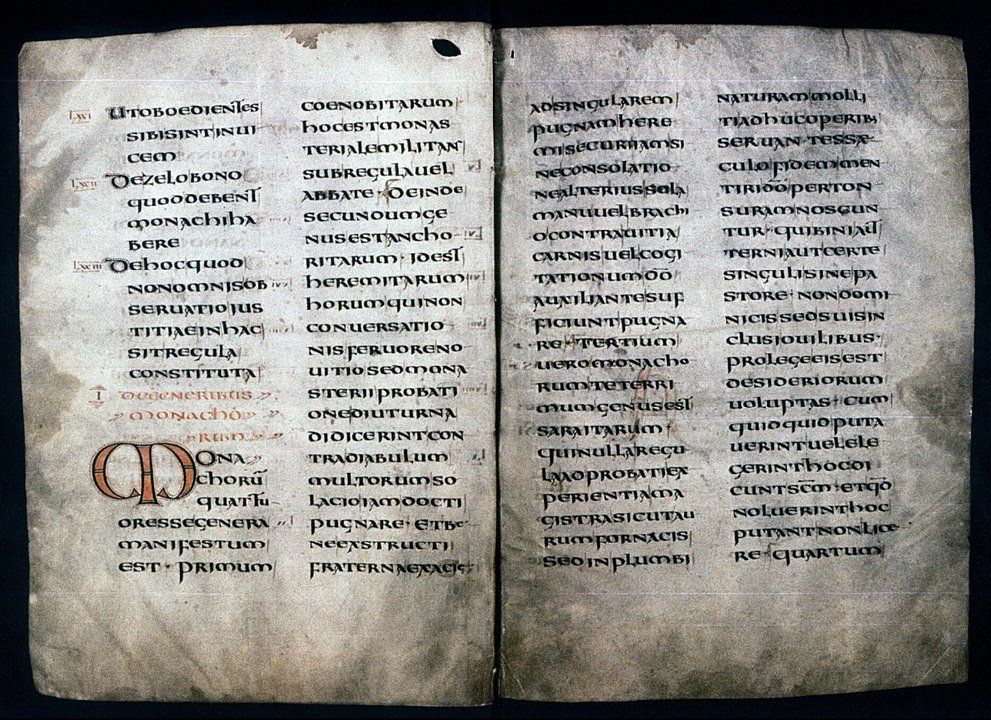

The oldest copy of the Rule of Saint Benedict, from the eighth century (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Hatton 48, fols. 6v–7r)

Photo above: Saint Benedict Presenting his Rule to Benedictine and Cistercian Monks in a Historiated Initial “O” from a Choirbook, 1394/95, Martino di Bartolomeo. Chicago Art Institute

The Holy Rule

The Holy Rule gives no biographical details but does offer numerous hints about the saint's character. It shows Benedict, like the monks of good zeal whom he wished to form (RB 72), to be passionate for God and for the things of God. From his experience of living in communities of monks, he learned that the little daily choices that one makes in ordinary life ultimately determine the basic orientation of one's whole life. For a Christian, as for every monk, the choice must be made for Christ again and again.

In the Rule, Benedict challenges his monks to make a fundamental choice to listen to the voice of Christ and to recognize that "the love of Christ must come before all else" (RB 4:21). The vow of stability and the detailed organization of life in community are meant to help the monk make the choice for Christ, day by day and moment after moment. The monk is instructed to see in these time-tested structures ample opportunities to choose for God and reject self-centered impulses.

Benedict was well aware of the pervasiveness of those self-centered tendencies, and his radical zeal for God is balanced by his loving concern for the individual monk with all his weaknesses. The saint knew that the brothers suffered from a variety of deficiencies and that all had need of forgiveness and mutual support on the journey to God.

He also possessed keen insight into the great differences that existed among individual monks; some were obedient, docile, patient, and perceptive, while others were undisciplined, negligent, stubborn, slow to learn, and even disdainful and arrogant. The more wayward the monk, however, the greater his need for the loving attention of the Good Shepherd to seek him out and heal him (RB 27:B). The abbot must fill the role of Christ in showing the utmost concern for straying sheep. He must avoid harshness and see himself as an instrument of Christ's healing love in his commitment to nurture the development of souls in the community.

The Rule also shows that St. Benedict was thoroughly grounded in the tradition of the Church with many quotations from or allusions to Sacred Scripture. The monks are urged to meditate extensively on Scripture as well as to read from the orthodox fathers of the early Church (RB 73:2-4). In writing the Rule, Benedict relied heavily on the already well-developed monastic tradition of the two previous centuries incorporating large sections of the Rule of the Master and borrowing teachings from other great monastic authors, such as Basil, Augustine, Cassian, and Caesarius of Aries. However, Benedict also did something new by blending the wisdom of the past in such a way as to respond to the conditions of sixth century Italy and giving the Rule enough flexibility to be adapted to the social and cultural circumstances of the Church for many centuries to come.

Benedict's Rule includes both spiritual teaching (mostly in RB 1-7, 72-73 and the Prologue) and practical regulations for the ordering of daily life in the monastery (mostly RB 8-71). He knew that both sound doctrine and disciplined practice were essential to authentic monastic life. For Benedict and the other ancient monastic leaders, monasticism was simply the Christian life lived in an especially intensive way in community as a response to God's persistent invitations. Thus, he called his document a "little rule for beginners." On the other hand, because of the passionate faith, the gentle compassion, and the invaluable practical wisdom embodied in the Rule, Benedict's way of monastic life became a tradition in itself spreading throughout the world, shaping Western civilization for the past 14 centuries.

Photo above: Study for St. Benedict, 1590, Bartolomeo Cesi. Chicago Art Institute

The Rule in History

During the life of Benedict, circumstances in Italy were turbulent because of the collapse of the Roman Empire and the repeated invasions by foreign tribes. This turbulence continued after Benedict's death. In fact, his monastery at Monte Cassino was destroyed by the Lombards about 581 AD. and remained abandoned until it was re-founded in 720.

The Rule itself, however, began to spread through much of continentalEurope and the British Isles. During the first several centuries of its existence, the Rule was frequently adopted in combination with other monastic rules. In almost every case, the Rule of Benedict eventually became the only norm of these monasteries, apparently because it compensated for the deficiencies of the other rules and rendered them unnecessary. By the eighth century England was sending missionaries abroad, and Benedictines like St. Boniface and St. Willibrord brought both Christianity and the Rule to Germany and other parts of the Frankish Empire. Charlemagne (768-814) established the Benedictine way even more firmly in Europe by decreeing that the Rule of St. Benedict was to be the standard for all monasteries of his empire.

During the often-unsettled conditions of the Middle Ages, Benedictine monasteries became centers where the arts andsciences flourished, good liturgy was nurtured, scholarship was prized, and ancient literature was preserved. Especiallyduring the tenth through the twelfth centuries, monastic houses multiplied and thrived as oases of learning and spiritual life. Although some Benedictine communities succumbed to laxity and the abuses of the times, there were reforms such as those at Cluny and Citeaux that gave new vigor to monastic life under the Rule.

Beginning in the twelfth century, new religious orders emerged to respond to the changing needs of Church andsociety so that monks and nuns of St. Benedict were no longer the exclusive representatives of religious life. During the Protestant Reformation, hundreds of European monasteries were forced to close their doors while some in Catholic areas were renewed in the spirit of Catholic reforms. Then, during the late 1700's and early 1800's, all but a handful of Benedictine houses were swept away by the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars. In the 1820's, however, enlightened Catholic rulers sought to reestablish the monasteries, which they realized had contributed so extensively to the faith and culture of Christian Europe. By 1900 Benedictine monastic life was once again well established in Europe, although not without the threats and restrictions of anti-Catholic governments.

The Rule and Benedictines in the United States

Among the Catholic rulers of the 1820's was King Ludwig I of Bavaria. In 1830 he reestablished the ancient Abbey of St. Michael in Metten, Bavaria. One of its monks, Fr. Boniface Wimmer, formerly a diocesan priest, discerned a call toinitiate monastic life in the United States with the purpose of serving the German immigrant population. After much contention with authorities, Fr. Boniface received permission to leave for America with 18 candidates for monastic life. In October, 1846, these men arrived in the area of Latrobe, Pennsylvania, and founded the first Benedictine monastery inNorth America and, soon thereafter, the college and seminary that came to be associated with the abbey.

Before his death in 1887, Abbot Boniface had made numerous foundations throughout the United States, many of which became independent monasteries. Since 1855, Saint Vincent has been the motherhouse of the American-Cassinese Congregation, which is largely the heritage of Boniface Wimmer's vision and tireless efforts. As of 1995, the congregation consists of 21 independent abbeys in Canada, Mexico, and the United States, as well as a number of dependent priories located as far away as Brazil, Taiwan, and Japan. Vowed to monastic life in these houses are over 1200 monks, who continue to adhere to the wisdom of a Rule written over 1450 years ago.

Photos above L-R: King Ludwig I of Bavaria; Saint Vincent Archabbey, Latrobe, PA; Archabbey Boniface Wimmer, O.S.B.