Covington’s Monte Cassino—home to the “smallest church in the world.”

Ripley’s Believe It or Not, 1922

Covington’s Monte Cassino

By Sir Stephen Enzweiler

EARLY HISTORY — Producing Altar Wine

In 1875, when Benedictine Archabbot Boniface Wimmer, O.S.B. of Saint Vincent Archabbey in Latrobe, PA, was having difficulty purchasing enough altar wine for his abbey. He decided to establish an operation in which the Benedictines could produce their own altar wine, and he hoped to find a suitable vineyard in the wine rich hills of Northern Kentucky.

Wimmer found a 76-acre tract of land on Prospect Hill directly above Latonia and overlooking old Peaselburg. Archabbot Wimmer’s nephew, Fr. Luke Wimmer, O.S.B., served as the community’s prior. Known as the old “Thompson Winery,” it had been a well-known producer of local wines for nearly a half century. On December 22, 1876, Archabbot Wimmer bought the property from the American Life Insurance Company of Philadelphia for $21,500 and named it Monte Cassino after the famed Italian monastery regarded as the cradle of the Benedictines.

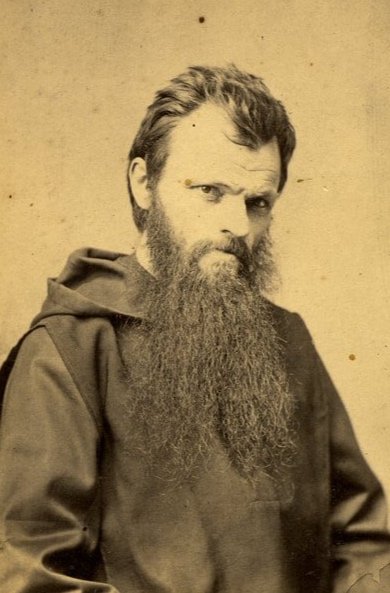

Photos above: Luke Wimmer, O.S.B. and a ca. 1880s view of the vineyards

By the following year, monks were dispatched to Kentucky and a monastery building was constructed. This was followed by a stone building for the fermentation and bottling of wines, along with barns and limestone-lined storage cellars dug into the hillsides. Archabbot Wimmer believed monasteries should be self-sufficient, and Monte Cassino would be no different. Thirty acres were used for grape cultivation and ten acres for pasturing cattle. The property had an orchard and gardens for food production. The monks rose before sunrise for morning prayers before heading out into the fields. The work was exhausting and backbreaking, with work beginning before sunrise and often going well past sunset.

The production of sacramental and commercial wines became the main source of income for the monks of Monte Cassino. In its early years, the operation produced 5,000 gallons of wine a year. The first pressing was for altar wine used in Catholic churches throughout the United States. The second and third pressings were for commercial sale under the label “Red Rose Wine.”

Photo above: Br. Albert Soltis, O.S.B.

Building the “world’s smallest church”

In 1901, Father Kopf, the monastery’s Superior, and Brother Albert Soltis, a German-born master mason, began work on a small fieldstone chapel situated behind the main monastery building overlooking the broad valley below. The intention was to provide a private space for monks exhausted from the day’s labors to rest and relax in solitude and prayer. The Benedictines consecrated the chapel to Mary the Mother of Jesus under the title, “The Sorrowful Mother.” Because of their German heritage, they installed a stained-glass window above the main door with the inscription, “Sehet ob ein schmerz Meiningen gliche,” meaning, “See if there is any sorrow like my sorrow.”

The chapel interior was only big enough for three monks at a time to worship within its small space. True to the Benedictine way, the inside was plain, the walls unadorned. Three wooden pre-dieux, or prayer benches, provided rest for occupants. The altar centerpiece was a crucifix and a statue depicting the Virgin Mary holding the body of her son in her arms. Candles and sunlight streaming through the side stained-glass windows were all that illuminated the interior.

For the next 16 years, the monks’ lives at Monte Cassino were consumed with working the vineyards—planting, pruning, harvesting. Exhausted at day’s end, they would enter the tiny chapel for mass, meditation or private prayer. In that sacred space, they understood their mission was not only the care of a physical vineyard, but the care of another kind of vineyard as well – the vineyard of humanity. “I am the vine and you are the branches,” they would’ve recalled Jesus saying. “I am the true vine, and my Father is the vinedresser. Every branch in me that bears no fruit, he cuts away; and every branch that bears fruit, he prunes to make it produce even more.” The next morning, it was back out into the fields. Work became their meditation; Monte Cassino Chapel, their solace.

Moving the Chapel

In 1916, life at the monastery began to change. Higher taxes levied on wine and declining grape production caused operations to suffer. The tiny chapel – witness of so many prayerful petitions over the years – no doubt saw increased use after that.

Then, Prohibition swept the land in 1920. The government permitted the monks to continue their wine-production, licensing the monastery as United States Bonded Winery No. 1, Sixth District of Kentucky. But it forbade commercial sales of the “Red Rose Wine,” which the Fathers had always depended on for their livelihood. Output was limited to only 1,000 gallons the first year, resulting in the loss of nearly four-fifths of their income. The second year, it lost even more. Production was halted. The turn of events caused the monks to discontinue all operations, and the brothers were eventually recalled to Saint Vincent Archabbey in Pennsylvania.

“See if there any sorrow like my sorrow,” the stained-glass still read over the abandoned doorway. But by 1924, there were no monks left to read it, no more masses to be said beneath it, no more prayers or devotions to be offered under its gaze. The tiny chapel languished along with the rest of the property. In 1925, the land was leased to the Frank Burkhart family, who produced grape juice there until 1953. In 1928, the barn burned down and other buildings fell into ruin. The stone-terraced vineyards became overgrown by thickets and the vines choked by weeds.

The tiny chapel, too, eventually fell to vandalism, despite the dignity of its purpose and seeming impenetrability of its stone edifice. It was stripped of its wooden door, its altar and statuary, and even the limestone steeple and cross. The side stained-glass windows that once let in the evening light for vespers were gone. And in the space above the missing front door, there was no stained-glass left to be read, only a gaping emptiness where the Virgin Mary’s words of sorrow once had been.

Chester F. Geaslen, a writer for the Cincinnati Enquirer and The Kentucky Post, began writing articles about the old chapel in the 1950’s. In one, he described it as “pillaged of all that could be carried away, even the little stone steeple with its hand chiseled cross. Blackened, is its stone arched interior from smoke and ash, as fires have been kindled on the stone floor where the little altar once stood.”

Finally, in 1964, the owner of the chapel was discovered. He was Fred Riedinger, a local plumber who had purchased the entire 76 acres property in 1957 from Saint Vincent Archabbey. Riedinger later sold the acreage – all but the tiny church – to Hanser Homes, Inc., a real estate developer. By 1964, the issue of its removal from the property was under consideration. Newspapers reported that Devou Park or Mother of God Cemetery were being considered. But in the end, Riedinger decided to donate the tiny chapel to Villa Madonna College in honor of his mother, Mrs. Alma Riedinger, and it would be moved to the future campus of Villa Madonna College in Crestview Hills.

The move got underway in April 1965. But transporting the 50-ton structure five miles across town without causing cracks in it proved to be a daunting task. Matt Toebben volunteered as contractor, and Carlisle Construction provided the semi-tractor trailer, flatbed and work crews for the job. The first task was to construct a frame beneath the structure that would enable them to lift it onto a flatbed trailer without cracking it. But days of rain had softened the ground and made it too dangerous to attempt the operation.

On Monday April 5, weather was favorable and the move commenced. The challenge was to carefully insert a semi-tractor trailer in a space just 15-feet wide between two newly-built homes to reach the chapel on the edge of the hill. The workmen lifted the structure onto the flatbed, then eased the tractor-trailer back between the houses, down an uneven corrugated ramp laid with thick timber to prevent the semi’s tires from sinking into the yard. Once on the street, it was checked and secured one last time. But rains began again and the operation was halted.

Two days later, the skies cleared enough and the move to Villa Madonna began anew. It took the procession four hours to make the trip. The route took it down Benton Road, along Highland Pike, Henry Clay Avenue, and south on Dixie Highway to Turkeyfoot Road. The tractor-trailer moved at less than 5 miles per hour, backing up traffic on Dixie Highway as it rolled slowly southward toward the turn onto Turkeyfoot. Workers were positioned atop the stone roof to lift telephone and electrical wires that draped across the streets. Monte Cassino Chapel arrived at its new home that afternoon and was lowered onto the slope overlooking the lake, where it has been ever since. The new Villa Madonna College was eventually built there; it was renamed Thomas More College in 1968.

Over the years, improvements and renovations were made to the tiny structure to try and preserve it. Today, a rusting iron security door and padlock guard its entrance. Yet, local residents and tourists still stop by on a regular basis to visit the tiny former house of worship, to feed the geese and enjoy the peaceful landscape, perhaps even to remember the monks who once prayed there and gave thanks for the vineyard and its bountiful harvest.

The Chapel Today

Montecassino, the famous Italian abbey where St. Benedict wrote his Rule, has been destroyed and rebuilt so many times that their motto is “Succisa Virescit”— “Having been cut down, it grows green.” The motto itself is testament to the resilience of Benedictine life through the centuries. The same can be said about Covington’s Monte Cassino Vineyard and Chapel which are both experiencing new life.

In 1968, the little chapel was moved to Thomas More University’s campus. Over the years, improvements and renovations have been made to the tiny structure. Today, the University plans to restore the chapel’s interior and exterior back to its former glory.

Monte Cassino Vineyard Today

The former Monte Cassino Vineyard grounds are also experiencing new life. For the past twenty years, the property’s owner Mark Schmidt has been breathing new life into the former vineyard grounds.

Known today as Monte Cassino Vineyards, sculpture now dots the property, and two rental properties are filled with antiques and artwork. Debris has been lovingly cleared from the old terraces, exposing the original 14 foot tall dry stacked stone walls. What was once the 1830’s summer kitchen, is now the Guest House, a tiny home, architectural gem, available here or through Airbnb for overnight stays. The most recent addition is a Tasting House, a private cabin sitting directly in the middle of the 20 acres available for private overnight stays for up to 6 people or for private events.

The newest project on the property, is a small museum, of all things, Covington, monk, and wine from the late 1800’s to early 1900’s.